TISL Press Release

Sri Lanka’s position in the annual Corruption Perception Index (CPI) has worsened in 2009 dropping to the 97th position among 180 countries. Last year Sri Lanka occupied the 92nd position. The Index, which focuses on corruption in the public sector, is conducted by Transparency International (TI), the global civil society organization leading the fight against corruption.

Sri Lanka’s score is at a low 3.1 (as against 3.2 last year) which indicates a serious corruption problem in the public sector in the country. Its score has continuously declined since 2002 when it was at 3.7.

Commenting on this score, Mr J C Weliamuna, Executive Director of Transparency International said that though CPI is perceptional, this is the most recognized and often quoted international index on corruption. “What we see is a clear indictment on Sri Lanka and the urgent need for major systemic changes to wipe out corruption. The lesson to learn from the CPI reading this year is that anti corruption should be nothing less than a national priority,” he said.

Commenting on the Index as a whole, Mr. Weliamuna also points out that the dictatorial regimes and countries plagued with internal conflicts are much worse in governance and therefore scored poorest in the Index.

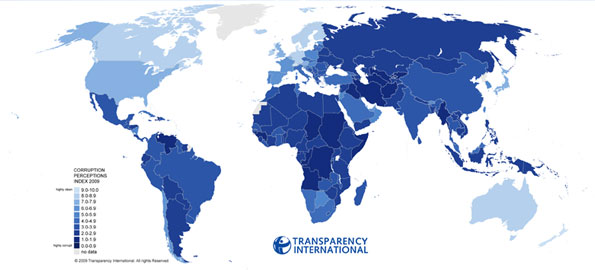

The CPI measures each country’s level of corruption and places it on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is highly corrupt and 10 low levels of corruption. It ranks countries in terms of the degree to which corruption is perceived to exist among public officials and politicians.

As for Sri Lanka’s neighbouring countries, India’s score remains at 3.4 while Maldives (2.5), Bangladesh (2.4), Pakistan (2.4) and Nepal (2.3) continue to be below 3.0. Bhutan’s score this year is 5.0.

Releasing the CPI, Chair of Transparency International, Hugette Labelle says that stemming corruption requires oversight by parliaments, a well performing judiciary, independent and properly resourced audit and anti-corruption agencies, vigorous law enforcement, transparency in public budgets, revenue and aid flows, as well as space for independent media and a vibrant civil society.

Explaining the significance of this year’s CPI in the global context, Transparency International says that as the world economy begins to register a tentative recovery and some nations continue to wrestle with ongoing conflict and insecurity, it is clear that no region of the world is immune to the perils of corruption. “At a time when massive stimulus packages, fast-track disbursements of public funds and attempts to secure peace are being implemented around the world, it is essential to identify where corruption blocks good governance and accountability, in order to break its corrosive cycle,” TI Chair stated.

A feature of this year’s CPI is that the vast majority of the 180 countries included in the index have scored below five.

Highest scorers in the 2009 CPI are New Zealand at 9.4, Singapore and Sweden at 9.2 and Switzerland at 9.0. These scores reflect political stability, long established conflict of interest regulations and solid functioning public constitutions. At the bottom of the index are Somalia (1.1), Afghanistan (1.3), Myanmar (1.4) and Sudan & Iraq (1.5). These results demonstrate that countries which are perceived as the most corrupt are also plagued by long-standing conflicts, which have torn apart their governance infrastructure.

TI Press Release

Corruption threatens global economic recovery, greatly challenges countries in conflict

Berlin, 17 November 2009 – As the world economy begins to register a tentative recovery and some nations continue to wrestle with ongoing conflict and insecurity, it is clear that no region of the world is immune to the perils of corruption, according to Transparency International’s 2009 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), a measure of domestic, public sector corruption released today.

“At a time when massive stimulus packages, fast-track disbursements of public funds and attempts to secure peace are being implemented around the world, it is essential to identify where corruption blocks good governance and accountability, in order to break its corrosive cycle” said Huguette Labelle, Chair of Transparency International (TI).

The vast majority of the 180 countries included in the 2009 index score below five on a scale from 0 (perceived to be highly corrupt) to 10 (perceived to have low levels of corruption). The CPI measures the perceived levels of public sector corruption in a given country and is a composite index, drawing on 13 different expert and business surveys. The 2009 edition scores 180 countries, the same number as the 2008 CPI.

Fragile, unstable states that are scarred by war and ongoing conflict linger at the bottom of the index. These are: Somalia, with a score of 1.1, Afghanistan at 1.3, Myanmar at 1.4 and Sudan tied with Iraq at 1.5. These results demonstrate that countries which are perceived as the most corrupt are also those plagued by long-standing conflicts, which have torn apart their governance infrastructure.

When essential institutions are weak or non-existent, corruption spirals out of control and the plundering of public resources feeds insecurity and impunity. Corruption also makes normal a seeping loss of trust in the very institutions and nascent governments charged with ensuring survival and stability.

Countries at the bottom of the index cannot be shut out from development efforts. Instead, what the index points to is the need to strengthen their institutions. Investors and donors should be equally vigilant of their operations and as accountable for their own actions as they are in demanding transparency and accountability from beneficiary countries.

“Stemming corruption requires strong oversight by parliaments, a well performing judiciary, independent and properly resourced audit and anti-corruption agencies, vigorous law enforcement, transparency in public budgets, revenue and aid flows, as well as space for independent media and a vibrant civil society,” said Labelle. “The international community must find efficient ways to help war-torn countries to develop and sustain their own institutions.”

Highest scorers in the 2009 CPI are New Zealand at 9.4, Denmark at 9.3, Singapore and Sweden tied at 9.2 and Switzerland at 9.0. These scores reflect political stability, long-established conflict of interest regulations and solid, functioning public institutions.

Overall results in the 2009 index are of great concern because corruption continues to lurk where opacity rules, where institutions still need strengthening and where governments have not implemented anti-corruption legal frameworks.

Even industrialised countries cannot be complacent: the supply of bribery and the facilitation of corruption often involve businesses based in their countries. Financial secrecy jurisdictions, linked to many countries that top the CPI, severely undermine efforts to tackle corruption and recover stolen assets.

“Corrupt money must not find safe haven. It is time to put an end to excuses,” said Labelle. “The OECD’s work in this area is welcome, but there must be more bilateral treaties on information exchange to fully end the secrecy regime. At the same time, companies must cease operating in renegade financial centres.”

Bribery, cartels and other corrupt practices undermine competition and contribute to massive loss of resources for development in all countries, especially the poorest ones. Between 1990 and 2005, more than 283 private international cartels were exposed that cost consumers around the world an estimated US $300 billion in overcharges, as documented in a recent TI report.

With the vast majority of countries in the 2009 index scoring below five, the corruption challenge is undeniable. The Group of 20 has made strong commitments to ensure that integrity and transparency form the cornerstone of a newfound regulatory structure. As the G20 tackles financial sector and economic reforms, it is critical to address corruption as a substantial threat to a sustainable economic future. The G20 must also remain committed to gaining public support for essential reforms by making institutions such as the Financial Stability Board and decisions about investments in infrastructure, transparent and open to civil society input.

Globally and nationally, institutions of oversight and legal frameworks that are actually enforced, coupled with smarter, more effective regulation, will ensure lower levels of corruption. This will lead to a much needed increase of trust in public institutions, sustained economic growth and more effective development assistance. Most importantly, it will alleviate the enormous scale of human suffering in the countries that perform most poorly in the Corruption Perceptions Index.